Text messages and other non-email, electronic communications have become increasingly important in securities fraud matters. These communications are often sent from personal mobile devices and often provide key evidence. It has become clear that the most interesting, and sometimes most problematic, communications often do not take place via email.

Messages sent via text and other messaging applications are increasingly being relied upon as evidence in securities fraud investigations and litigations. Since 2021, the SEC has investigated large trading firms for “off-channel communications,” business-related communications through platforms that are not monitored or firm-approved (e.g., text messages). As a result, the SEC has fined financial firms a total of over $1.7 billion for failure to maintain and preserve electronic communications.[1]

Following a civil trial in June 2024, now-bankrupt Terraform Labs agreed to a $4.47 billion settlement to resolve an SEC lawsuit after its co-founder was found liable of fraud. This settlement will be treated as an unsecured claim in Terraform’s Chapter 11 case.[2] At trial, the SEC offered text messages among employees that detailed a secret arrangement between Terraform and a crypto trading platform to prop up Terraform’s cryptocurrency before it collapsed into evidence. These text messages included a message from the head of communications stating that the co-founder “said if [crypto trading platform] hadn’t stepped in we actually might’ve been f-ed.” The business development head responded “I know. They saved our a–.” SEC v. Terraform Labs PTE LTD, 23-cv-1346 (JSR) (July 31, 2023). After a discussion with a crypto trading platform, the communications head texted “Spoke with [co-founder], we’re going to deploy $250 million from stability reserve through [crypto trading platform] to stabilize the peg.” He followed up with “[crypto trading platform] has already started buying. May not need the entire $250 million.” The next day, Terraform’s official Twitter account posted “Terra’s not going anywhere. $1 parity on UST already recovered.” This is just one example of a case where the preservation, collection, and production of text messages were critical to its outcome.

There are, at least, three areas where companies should examine their internal policies concerning mobile device data: (1) policies and procedures for mobile device use and “off-channel” communications; (2) preservation and collection obligations regarding employee communications on mobile devices (including personal devices) in litigation; and (3) content of mobile messages that will be produced in litigation.

Policies and Procedures

Internal policies governing the use of mobile devices and any “off-channel” communications should be in place and discussed with employees as a critical part of onboarding, as well as ongoing HR, and employee policies. Business-related communications via messaging applications that are not monitored or maintained by their employers has dramatically increased since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. For those working in financial services, including investment bankers and securities traders, the existence of communications about firm business on messaging applications like iMessage, WhatsApp, Slack, or Signal risks scrutiny and fines from government regulators. Additionally, employees at financial firms may be more likely to send problematic or even illegal messages through unmonitored channels if they believe the messages will not be subject to scrutiny, particularly on their personal devices. These messages may give rise to civil liability to both regulators and private plaintiffs.

When developing a mobile device policy, companies should consider the following questions:

- Whether employees use company-issued devices or, if not, is there a policy for employees who bring their own devices (a “BYOD” policy)?

Many employees prefer to use a single device for both personal and work-related purposes, even when a corporate device is offered. They should, however, be informed of the risks of intermingling business and personal communications, particularly if their good friends are also business contacts. A friendly chat about the state of the industry could blur the lines into business-related communications. In United States v. Blaszczak, a CMS employee remained friends with Blaszczak, the defendant, after he left the organization to work for a hedge fund. 947 F.3d 19 (2d Cir. 2019). The employee then provided inside information via phone calls, emails, and text messages on CMS rate changes that lowered reimbursement rates in the course of his friendship with Blaszczak.

- Are employees required to cooperate with requests for access to their devices during litigation?

This consideration underscores the requirement for a BYOD policy or corporate device policy. Either of these policies should specifically articulate the requirement of providing access to business-related communications, documents, photographs and other data stored on mobile devices in case of litigation. Policies should also discuss an employee’s expectation of privacy with respect to the personal data on a device that is used for business purposes. This will also help employees make informed decisions about how and when to communicate on a mobile device for work purposes before the information is discoverable.

- How are the mobile device policies enforced? Which applications are employees allowed to use for work purposes?

It is important to consider mobile device management and mobile device data archiving tools, and other corporate access to mobile devices that will be used for business purposes. The software can allow companies to remotely monitor, update, secure, and even delete data from personal smartphones or tablets that are used for business purposes. Employers can designate applications for business use. As an example, Microsoft Office 365 provides a full suite of applications, including Outlook, Teams, and applications to view and edit documents. These and other similar applications can be protected by passwords and/or two-factor authentication. Importantly, data from applications designed for corporate use can also be stored on a company server. Employee access can be granted or revoked remotely, and the data is preserved in the event that a device is lost or damaged. Additionally, if the employee has only used corporate applications such as Teams, Slack or Skype for business-related messaging (rather than texts or other platforms where personal communications are mixed in), it will not be necessary to collect messaging data from the employee’s personal device during litigation because the company will already have that data on the company’s servers.

- What are the policies and procedures for departing employees?

If the departing employee used a corporate device, internal policies should require the employer’s IT department to verify whether there is an obligation to preserve the data on the device before it is erased. If the departing employee used a personal device, the company should collect any data that may be relevant to an ongoing or foreseeable litigation. If it is not possible to collect the data prior to the employee’s departure, the employee should be reminded of the potential obligation.

Preservation and Collection

In litigation, companies are required to produce data that is within their possession, custody, and control. As part of this determination, courts will consider the following factors when it comes to mobile data: (1) whether the employer issued the devices, (2) how frequently the devices were used for business purposes, (3) whether the employer had a legal right to obtain communications from the devices, and (4) whether company policies address access to communications on personal devices. See, e.g., Miramontes v. Peraton, Inc., No. 3:21-CV-3019-B, 2023 WL 3855603 (N.D. Tex. June 6, 2023).

Given the increasing use of mobile communications to conduct business, particularly in the era of remote or hybrid work, it is reasonable to expect that mobile-device data will be part of a discovery request in a securities class action litigation. Companies have the same obligation to make reasonable, good faith efforts to preserve mobile data, including data on employee personal devices, as with any other type of data that may be relevant to a litigation.

Here are some considerations related to preservation and collection of mobile data:

- What communications may be relevant?

Any employee who may possess information relevant to the litigation may also possess relevant mobile data. Counsel, along with forensic examiners, will often interview employees who likely have information relevant to the litigation to identify the type and frequency of business communications, applications used for business purposes, and the amount of potentially-relevant information the employee possesses on their mobile device.

In Boston Retirement System v. Uber Technologies, Inc., the defendant produced text messages from an employee related to an alleged securities fraud. No. 19-cv-06361-RS (DMR), 2024 WL 555891 (N.D. Cal. Feb. 12, 2024). The plaintiff filed a motion to compel additional text messages from other employees, but the court denied the motion because the employees stated in their interrogatories that they did not communicate about business via text message and they had not texted about the subject matter of the lawsuit.

Other details may help focus the text message collection, including the relevant time periods of the conversation (e.g., the time periods surrounding a particular trade or release of information), the communication platforms used (e.g., iMessage, WhatsApp, Signal) and the parties of interest.

In United States v. Buyer, the defendant was accused of trading on inside information related to a proposed acquisition of Navigant by Guidehouse. 22 CR. 397 (RMB) (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 14, 2023). He admitted to phone calls and text exchanges with a Guidehouse employee right before he purchased Navigant stock. The government also presented a Signal message from the defendant as evidence of an attempted coverup. The message read: “I need to see you. Please, I will catch the next flight. I was interviewed and told them I bought . . . .” The defendant had intended this message to be deleted after 5 minutes.

- What is the level of technical sophistication of the employees?

Data may be inadvertently lost in a number of ways, including: failure to follow a litigation hold, accidental deletion of messages (e.g., auto-delete), upgrading the device to a different model without transferring or backing up its data, or performing a factory reset. It is important to assess whether to trust an employee to properly manage their device settings, or whether it may be necessary to preemptively collect mobile data to ensure that it is preserved.

It is important to be aware of the default settings in place before a litigation hold is in effect, both on mobile devices and corporate servers, as these settings may need to be adjusted. Mobile device management systems and applications backed up to a remote server (e.g., Microsoft Outlook and Teams) make it easier to preserve data at a global level and eliminate user error. If an employee uses text messages or other messaging apps to communicate for business purposes, it will be important to instruct the employee to change their device settings to ensure no information will be inadvertently deleted, particularly because courts will likely consider business communications to be within the employer’s control.

Although proper preservation of mobile data often does not require a substantial effort, a failure to adequately preserve relevant mobile data can result in monetary sanctions and/or adverse inferences at trial. In Hunters Capital, LLC et al v. City of Seattle, the Seattle mayor deleted thousands of text messages from her employer-owned phone, claiming that this was partly because she inadvertently set all text messages to auto-delete after 30 days. 2023 WL 184208 (W.D. Wash. Jan. 13, 2023). The court issued an adverse inference instruction to the jury, telling them they could presume that the text messages were unfavorable to the defendant.

- What are the technical requirements and procedures for collection?

The collection process can often be performed remotely, but the forensic examiner will sometimes require physical possession of the device. If the mobile data in question is backed up on a remote server, it can be collected remotely, and with minimal disruption to the employee. Apple iPhone data can typically be collected remotely through iCloud, while Android data typically must be collected from the device itself. Messages and other data from mobile devices that are not available on a remote server are typically collected through a logical extraction, which creates a forensic image of the entire phone, preserving the integrity of the data at the time of the collection. Importantly, however, logical extraction cannot recover deleted files or be used on a locked device. Ephemeral messaging applications (e.g., Signal, Telegram), which do not permit archiving or remote storage of messages, can only be collected through screenshots or manual collection methods. Additionally, if an employee has very few relevant messages, a screenshot or other manual collection may be appropriate.

After a logical collection, the collected data is encrypted and is not in a viewable format until it is processed. Accordingly, none of the employee’s text messages or other application data are readable at this stage. Data collected through screenshots or other manual methods will be in an immediately viewable format. Messaging data and other data from sources identified as relevant to the litigation is processed and loaded into a database where it can be viewed by counsel. The employee can also identify their business contacts, further limiting what outside counsel will view and helping to ensure the privacy of their personal messages.

Content of Mobile Messages

In litigation, as opposed to regulatory investigations, the parties may have more room to negotiate the scope and relevancy of mobile messages to be produced to the other side. The legal team can opt to produce only the relevant portions of message threads, redacting non-relevant messages and images (including personal messages and photos). In some instances, however, it may be necessary to produce non-relevant messages to provide context. See Al Thani v. Hanke, No. 20 CIV. 4765 (JPC), 2022 WL 1684271, at *2 (S.D.N.Y. May 26, 2022) (“a single text message, standing alone, is oftentimes meaningless without other messages in the text chain to provide context”). Additionally, one-off messages, gifs or emojis can sometimes provide important evidence if they are understood to have a certain meaning in the relevant industry-specific communications.

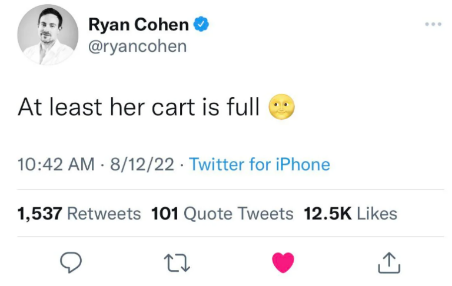

For example, in the case of In re Bed Bath & Beyond Corp. Securities Litigation, a message with an emoji provided potentially key evidence of securities fraud. U.S. Dist. LEXIS 129613 (D.D.C. July 27, 2023).

In denying a motion to dismiss, the court noted: “Some online communities understand the smiley moon emoji to mean ‘to the moon’ or ‘take it to the moon.’…In other words, according to Plaintiff, Cohen was telling his hundreds of thousands of followers that Bed Bath’s stock was going up and that they should buy or hold. They did so, sending the price soaring.”[i] Similarly, in Friel v. Dapper Labs, Inc., for example, the court reasoned that “the ‘rocket ship’ emoji, ‘stock chart’ emoji, and ‘money bags’ emoji objectively mean one thing: a financial return on investment.” No. 21-cv-5837, 2023 WL 2162747, at *17 (S.D.N.Y. Feb. 22, 2023). Even metadata can contain damaging information, as in the case of the now-defunct cryptocurrency exchange FTX, where Sam Bankman-Fried and other staff had a Signal chat group named “wire fraud.”[3]

Employees may feel uncomfortable about the information that is included in a forensic image of their mobile device, particularly if it is a personal device. Personal data such as photos, banking information, and other personal data stored on their device is collected even when it is not relevant in any way to the litigation. Although the majority of the information will never be viewed, and forensic vendors take extensive security precautions (e.g., security certifications, double layers of encryption, locked storage within locked facilities), some employees may still feel uncomfortable about the collection of information from their personal devices. This underscores the importance of informing employees what the collection process may entail when they sign a mobile device agreement, as described above, so that they can decide whether to use a personal device for work well before any litigation has begun.

Final considerations

Given the proliferation of these communications, and their probative value in the cases discussed above, it is undeniable that litigants in securities fraud cases need to have robust mobile data policies that address the content and retention of messages, applications used for messaging, and the obligations of employees to allow for collection, in addition to an IT infrastructure that facilitates all of the processes outlined above. It is also important to ensure that employees understand the risks of communicating about business on a personal device, and the discovery obligations related to those communications.

[1] https://www.reuters.com/legal/government/sec-sued-by-trade-association-details-record-keeping-probe-2024-06-06/

[2] https://www.reuters.com/legal/crypto-firm-terraform-labs-agrees-pay-447-bln-resolve-dispute-with-sec-2024-06-12/

[3] https://www.theguardian.com/business/2022/dec/13/sam-bankman-fried-ftx-signal-wirefraud-chat-alameda