by guest blogger Alexandra J. Roberts

It’s become known as the “sad beige lawsuit” or the case that asks the question “can you ever really own an aesthetic?” But the suit, in which 24-year-old influencer Sydney Nicole Gifford accuses another influencer, 22-year-old Alyssa Sheil, of copying both her posts and her style, may have an outsized effect on the law around online content creation. In a November ruling, a magistrate judge notes that the lawsuit “appears to be the first of its kind—one in which a social media influencer accuses another influencer of (among other things) copyright infringement based on the similarities between their posts that promote the same products.” Sydney Nicole LLC v. Alyssa Sheil LLC, 1:24-cv-00423-RP (W.D. Tex. Nov. 15, 2024).

In the complaint, filed in district court in Texas last April, Gifford describes how she uses social media and e-commerce platforms, including TikTok, Instagram, Amazon Storefront, and bio.site, to foster her “unique brand identity,” establish trust with her followers, and curate and promote thoroughly-researched and “thoughtful lists” of products she recommends. Gifford accuses Sheil of adopting the same “neutral, beige, and cream aesthetic” that comprises her brand, featuring many of the same products, and copying Gifford’s style and captions. Both women are from Texas, though Gifford has since moved to Minnesota, and the two met up several years ago to discuss business strategy and participate in a photoshoot together; Gifford claims Sheil blocked her on Instagram and TikTok shortly after their collaboration, making it easier for Sheil to copy Gifford’s content without Gifford noticing.

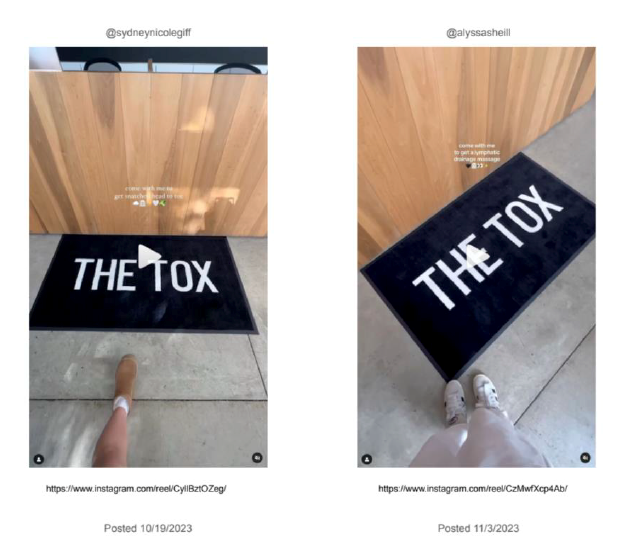

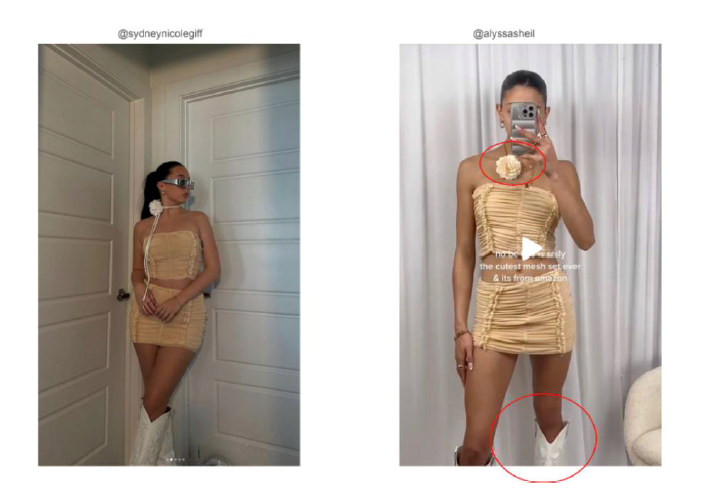

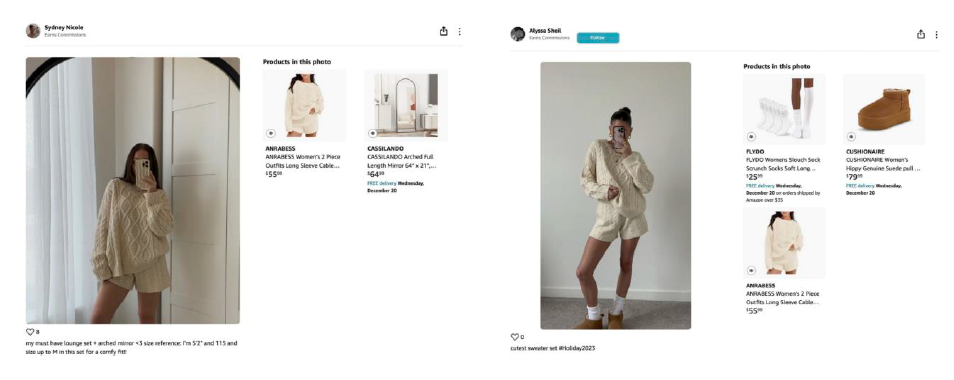

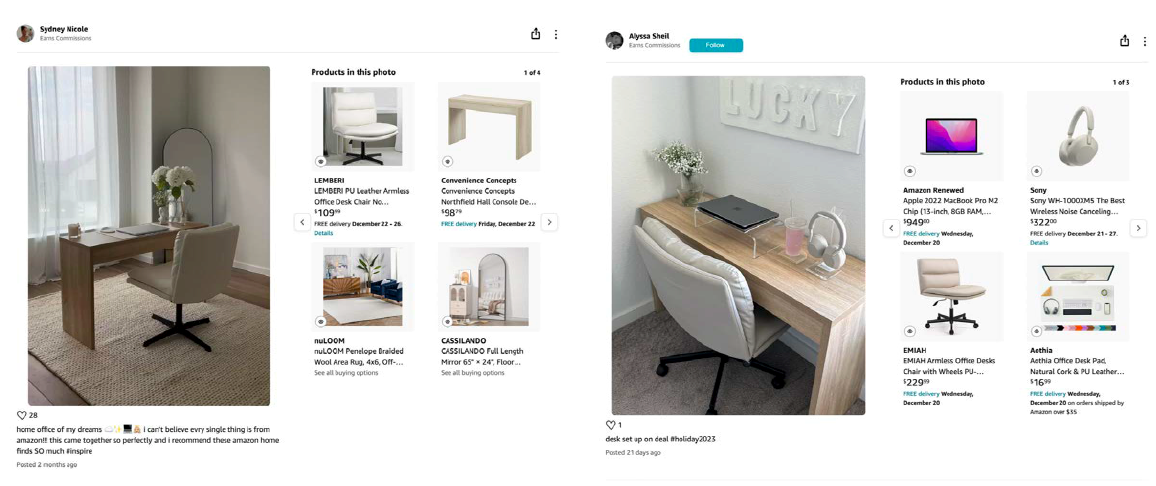

Sheil allegedly models herself on Gifford in myriad ways, from how she dresses, styles her hair and makeup, poses, and speaks, to how she decorates her home, to the language and themes of her posts, to the products she features and the places she goes. Gifford even claims Sheil got the same flower tattoo as Gifford in the same spot on her left bicep. The complaint includes a number of side-by-side comparisons of Gifford’s and Sheil’s posts, such as the following (with Gifford’s posts appearing on the left and Sheil’s on the right):

As with “copycat” cases in other industries, Gifford’s complaint is a grab bag of claims, including direct and vicarious copyright infringement, violation of the DMCA in the form of removal of copyright management information, trade dress infringement, misappropriation of likeness, tortious interference with prospective business relations, federal unfair trade practices, and unjust enrichment. Before suing, Gifford registered a number of works with the US Copyright Office, including 140 photos and at least 18 videos.

On first read, I thought the suit was a stretch, and I’m not the only one. Misappropriation requires the unauthorized commercial use of someone’s name, image, or likeness; Gifford would need to show that simply by copying her outfits and hairdos, Sheil was using Gifford’s likeness. (Incidentally, as discussed in The Verge, Gifford identifies as a white Hispanic woman, while Sheil is Black. Neither woman has a particularly distinctive look—unlike, for example, Lucianne Walkowicz, the astronomer who sued American Girl over a “Luciana” doll that featured the same purple-streaked hair and silver holographic shoes for which Walkowicz was known).

Trade dress protection, meanwhile, is available for product packaging, product design, and restaurant and store décor, and even in those categories owners need to establish the trade dress is nonfunctional and serves as a consistent source indicator. Using a neutral color palette across social media posts seems unlikely to qualify for protection, especially given how that color scheme reflects a much broader trend, often called the “clean girl” aesthetic and epitomized by much more widely-followed celebrity influencers like Kim Kardashian and Hailey Bieber.

And while Gifford’s posts are protectable under copyright law, works like a photo of feet near a store’s welcome mat or a curated list of items for sale on Amazon reflect minimal creativity and should be subject to only thin protection and therefore difficult to infringe.

Sheil moved to dismiss six of the eight causes of action. Last month, a magistrate judge dismissed the claim for tortious interference with contractual relations, finding Gifford had alleged neither actual breach of contract nor intent to cause such a breach; he also dismissed the unfair competition and unjust enrichment claims as preempted by the Copyright Act.

Surprisingly, the magistrate judge declined to dismiss the other challenged claims. And on December 10, the supervising district judge adopted the magistrate’s report and recommendations.

In ruling that Gifford’s vicarious copyright infringement claim was sufficiently pleaded, the magistrate judge explained that Gifford had adequately pled that Sheil was responsible for the allegedly infringing content on her platforms; that she supervised and exercised control over her followers’ ability to access, view, and download that content; and that she had a direct financial interest in the infringing activity because it corresponds to higher views, engagement, sales of products, and commissions. In other words, Sheil’s composition of similar social media posts and her choice to share them with her followers might subject her to liability for both direct and vicarious copyright infringement, and her followers could be found to infringe Gifford’s copyrights directly just by “accessing, downloading, interacting with, and/or viewing the infringing content.”

Next, in finding Gifford sufficiently stated a claim under the DMCA, the judge held that Sheil did not need to post or re-post identical works to create liability; instead, by posting content similar to Gifford’s without including Gifford’s social media handle—which constitutes copyright management information (CMI)—and knowing or having reasonable grounds to know that such omission would conceal her infringement, Sheil might violate the DMCA.

And finally, in declining to dismiss Gifford’s misappropriation claim under Texas law, the judge found Gifford sufficiently alleged that Sheil appropriated her name or likeness for the value associated with it, Gifford could be identified from the posts, and Sheil received some advantage from the misappropriation. The judge apparently found plausible Gifford’s allegation that Sheil imitated her “outfits, poses, hairstyles, makeup, and voice” in a way that enabled Gifford’s followers to identify Gifford as the person whose identity was appropriated. Counter to Sheil’s argument that she didn’t use Gifford’s actual name, image, or voice, the judge cited case law holding that it isn’t necessary to use a person’s image or full name to “symbolize or identify” that person and capitalize on their publicity right. Just as a race car could identify the car’s professional driver, a robot game show hostess in a blonde wig could identify Vanna White, and a reference in a shirt ad to “Don’s henley” constituted a reference to musician Don Henley, Sheil—in donning a “beige skirt and strapless top set” with white cowboy boots and a flower clip around her neck and blocking her face with her phone—could also be found to “identify” or “pass herself off as” Gifford.

Surprising or not, deeming any of these categories of claims plausible for creators posting similar content has serious implications. Influencer marketing has become increasingly central to commerce. Social media is built on trends, and as soon as users click or linger on a post, algorithms are quick to push related content into their feed. Intellectual property law has not traditionally protected the way someone styles their hair, makes up their face, or decorates their home, whether or not those choices are photographed and shared. Influencers who partner with Amazon or other brands are choosing from among the same set of products to endorse, so their curated lists may overlap and their descriptions of the products will too.

Influencers take inspiration from each other and from broader beauty, design, and product trends, tailoring their content to provide what their followers want and reviewing the same viral products as their peers. Will they now find their expression chilled as they fear being accused of infringement or misappropriation? Given the meteoric rise of dupe marketing, will content creators suggesting lower-cost alternatives to popular products have to watch their backs too? Some attorneys speculate that the sad beige influencer litigation “could lead to a deluge of similar suits.” It’s no wonder this case has generated coverage everywhere from Bloomberg to People Magazine—in monochromatic living rooms across the world, content creators are watching and waiting.