The University of Windsor’s agreements with encampment protesters and a student group have rightly raised concerns about antisemitism given their double standard treatment of Israeli institutions and impact on academic freedoms. While much of the initial emphasis has focused on the ill-advised decision to effectively establish a ban on agreements with Israeli institutions and establish conditions not required for any other country, there is another aspect that deserves attention since it undermines the university’s position as a neutral forum for discussion, debate and learning. In light of the diversity of views on campus and the desire for mutually respectful dialogue and engagement, many universities have tried to remain neutral on matters of sensitive politics post-October 7th. But by committing to engage in political advocacy, including issuing a political letter to the governments, lobbying other universities, and releasing a highly charged public statement, Windsor has abandoned the widely accepted fundamental principle of institutional neutrality, thereby constraining academic freedom and freedom of expression on campus.

The starting point for current thinking on institutional neutrality often dates back to the late 1960s and the University of Chicago’s Kalven committee report. The committee was asked to prepare “a statement on the University’s role in political and social action.” It concluded “there is no mechanism by which it [the University] can reach a collective position without inhibiting that full freedom of dissent on which it thrives.” While the report identifies a few exceptional instances where a position may be needed (such as if the very mission of the university is threatened), it states:

These extraordinary instances apart, there emerges, as we see it, a heavy presumption against the university taking collective action or expressing opinions on the political and social issues of the day, or modifying its corporate activities to foster social or political values, however compelling and appealing they may be.

This thinking has been repeatedly adopted by other universities. For example, a report from the University of Waterloo Task Force on Freedom of Expression and Institutional Engagement released just last month cites the Kalven committee report in adopting the following principle on institutional neutrality:

The University adopts the principle of institutional neutrality. This means that the University’s president, provost, other senior administrators, deans, and authorized spokespersons should refrain from making statements on social, political, or moral issues, on behalf of the University, out of concern that such statements politicize the University and constrain the academic freedom and the freedom of expression of individuals in the University Community.

The Task Force notes that to do otherwise may result in “adverse effects, which would include silencing dissent and minority voices.” Similar concerns were even raised at the University of Windsor earlier this year during a Senate presentation from James L. Turk of the Centre for Freedom of Expression, who cited the Kalven committee report as the standard for institutional responsibilities on expression. Days before Turk had co-authored a public letter to all Canadian universities and colleges stating that “it is not the role of the university to wade into political matters locally or globally that extend beyond its immediate purview, which is the operations of the university itself.”

Faculty unions have adopted the same position. David Robinson, the Executive Director of the Canadian Association of University Teachers, cited the Kalven committee report in a University Affairs interview, stating:

The role of universities is to be a place where debate and conversations about this can exist. The only way we are going to resolve conflict is through discussion and resolution, not taking one view or the other.

Despite the widespread acceptance of the principle of institutional neutrality and the risk that adopting political positions has to freedom of expression by the university community, the University of Windsor encampment agreements unquestionably violate this principle, doing precisely what the Kalven committee warns against as they express political opinions and modify corporate activities. In fact, by making different commitments in the two agreements – the agreements with the student association and encampment protesters are not identical – the University signals that its political position isn’t really the University position at all but rather reflects a capitulation to unlawful encampment protesters and their supporters. Signalling for support for such a dangerous precedent will not age well.

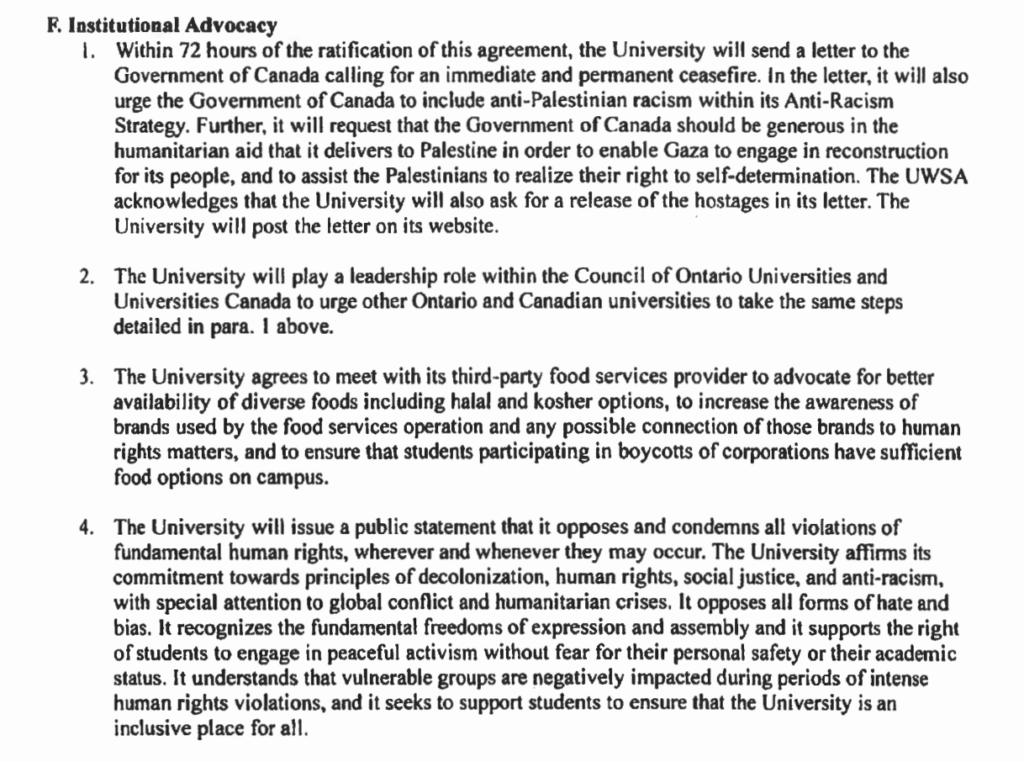

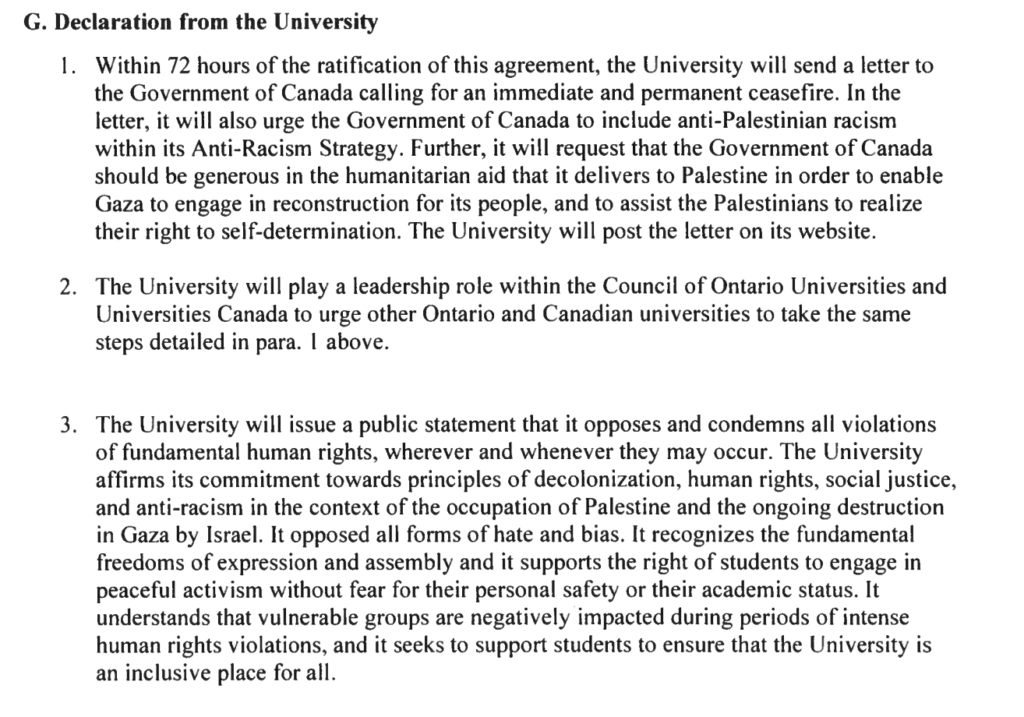

Both agreements include a comparable section that is titled “Institutional Advocacy” in the student agreement and “Declaration from the University” in the encampment protester agreement.

UNIVERSITY OF WINDSOR STUDENTS ALLIANCE (UWSA) agreement, https://www.uwindsor.ca/sites/default/files/2024-07-10_uw-uwsa-lzt-agreements.pdf

WINDSOR LIBERATION ZONE TEAM agreement, https://www.uwindsor.ca/sites/default/files/2024-07-10_uw-uwsa-lzt-agreements.pdf

The provisions leave no doubt that the goal is for the university to abandon neutrality and engage in several different advocacy initiatives. These include issuing a letter to the Government of Canada urging a ceasefire, adoption of anti-Palestinian racism within its anti-racism strategy, delivering generous Palestinian humanitarian aid, and providing assistance on Palestinian self-determination. The university also agrees to urge all Canadian universities to adopt the same position and commits to public statement on human rights, decolonization, and social justice.

There are some differences, however. The student agreement states that its letter will include a request to release the hostages. There is no such reference in the encampment protester agreement. The student agreement also features a provision on access to halal and kosher food options. Left unstated in a reference to boycotts is that there have been efforts to ban “Zionist” supporting food services that risks leaving Jewish students without access to kosher food on campus.

Conversely, the encampment protester agreement situates the public statement differently. While the student agreement speaks generally to support for human rights, decolonization, anti-racism, and social justice, the encampment protester agreement limits most of these issues to the “context of the occupation of Palestine and the ongoing destruction in Gaza by Israel.” It is not clear which approach the university will take, but these are clearly not the same thing and require the University to articulate a political perspective that does not reflect the views of the full University community.

Much like how for some the maxim of believing all women seemed to include a shameful exception for Israeli and Jewish women with regard the sexual assaults of October 7th, it appears there is also an Israeli and Jewish exception to institutional neutrality. But no university should so easily cast such a fundamental principle aside. Neither agreement has received formal approval from the University’s Senate or Board of Governors. While the University maintains these are “operational” agreements that do not require such approval, the implications for the University, its reputation, and its commitment to fundamental principles widely respected by universities worldwide has been placed at risk. That surely extends beyond just operational questions and it falls to University leadership to undo the agreements that undermine academic freedoms and raise disturbing antisemitism concerns.