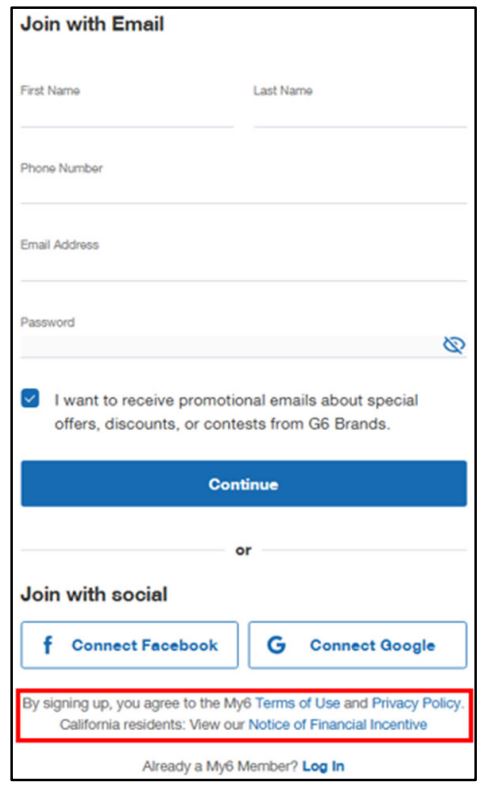

This is a Meta pixels case agains the G6 hotel chain (a/k/a Motel 6). G6 sought to arbitrate the case per its TOS. G6 presented the court with a screenshot of Motel 6’s standard account creation process:

G6 added the red box for the court. This screenshot looks like a standard sign-in-wrap with a good chance of enforceability. Normally, we’d expect the court to pixel-police this screen, looking for defects. That didn’t happen here.

Instead, the plaintiff pointed out that it was possible to create a Motel 6 account other ways, including the checkout process and via the mobile app–and neither of those screens referenced the TOS or privacy policy. “Because these pages provide no notice whatsoever of the Terms of Use or Privacy Policy, the checkout and mobile app sign-up pages do not meet the standard for constructive notice.”

The plaintiff didn’t explain which of the three doors they came through, but they didn’t have to. G6 invoked the TOS, so G6 bore the burden of showing that the plaintiff agreed to it:

Defendant has failed to provide adequate evidence to establish which version of the sign-up page Plaintiff used when she signed up for her Motel 6 account. Regardless of whether the website’s sign-up page that Defendant cites may have provided Plaintiff constructive notice, Defendant has not established by a preponderance of the evidence that Plaintiff signed up using that method, as opposed to using either of the two sign-up pages which provided no notice.

Thus, the court denies arbitration of this case.

The court nevertheless dismisses the case because the privacy policy extensively described the Meta pixel and the court says the plaintiff “consented” to the privacy policy. This conclusion confiused me because the court doesn’t explain how the plaintiff consented to the privacy policy. The court only says that “Plaintiff does not argue that she was not on notice of the privacy policy nor that she did not agree to it.”

Say what? The court just held that the plaintiff didn’t have constructive knowledge of the TOS or privacy policy and denied arbitration on that basis, so the court’s position seems facially inconsistent. At minimum, the court shifted the burden to the plaintiffs to prove they didn’t know of the privacy policy when G6 had the burden to show the plaintiff knew of the TOS. I don’t understand that shifting burden, nor did the court explain it.

* * *

G6 created what I call a “leaky” formation process. G6 had a primary account creation process that it tried to button up legally, but the process had “leaks” because users could follow secondary account creation processes where the TOS wasn’t properly implemented. In other words, users could reach the finish line (the account creation) without going through the prioritized process, and users who took an alternative route are not governed by the TOS. Indeed, as this case shows, unless the defendant can prove the plaintiff went through the desired process, the mere existence of TOS formation workarounds can categorically undermine the TOS formation for everyone–even users who actually did through the primary process.

A common source of potential “leaks” is any option for users to log in using third-party credentials, such as a “join with Facebook” option. Those login options create a new userflow that may not entirely be in the control of the website trying to form the TOS; and if users divert from the primary userflow to one of these options, they can easily “leak” out of the process.

My preferred solution is to build an account creation or checkout process that forces everyone through an identical TOS formation screen. In other words, all of the various navigation pathways take the users to a chokepoint where the TOS is formed. That way, the lawyer can superintend that screen and only make any necessary changes in one place.

A single chokepoint may not be possible; for example, often web and mobile userflows are necessarily different. In that case, the lawyer has to superintend every screen that relates to the TOS formation process. This poses a bigger challenge because there may be multiple userflows that are constantly changing outside the lawyer’s purview; and if the lawyer needs to make a change, there may be multiple places to make it.

Whatever the inplementation, it is the lawyer’s responsibility to ensure that there are not any leaks in the TOS formation process. This is true even though lawyers often review only the screens flagged for review by the engineering and marketing teams. Not good enough. The lawyer must independently navigate every userflow, using multiple devices and browsers to look for possible layout issues with each, to confirm that TOS formation meets the legal standard. As I tell my students, it doesn’t matter if you’ve created the most brilliantly drafted TOS if your formation process fails you.

Case Citation: Snyder v. G6 Hospitality LLC, 2025 WL 1254382 (C.D. Cal. April 14, 2025)