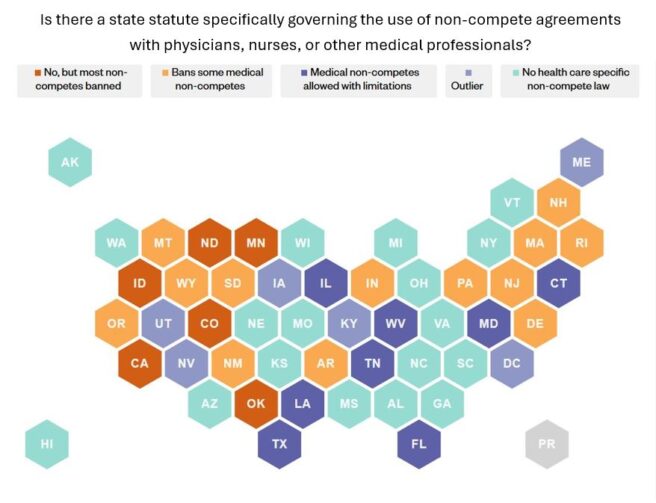

In the wake of the Federal Trade Commission’s recently failed attempt to ban non-compete agreements between employers and workers,[1] individual states have once again taken up the mantle of further regulating and limiting their use. These states’ new efforts have appeared with greatest frequency in the health care sector.

In states where noncompete laws have recently changed, legislatures appear to be working towards striking a balance between the various rights and interests of the affected stakeholders. These rights and interests may include a company’s right to protect its legitimate business interests (such as confidential information, customer relationships, and company goodwill), a health care practitioner’s right to make a living, a community’s interest in maintaining the broadest scope of medical services available, and the interest of patients to maintain continuity of care.

As a result, these new laws have created a kaleidoscope of noncompete restrictions and limitations that will require employer and contractors’ close attention to ensure that arrangements with health care practitioners in any jurisdiction are consistent with governing law. It remains to be seen how these restrictions will distort the market and impact incentives.

Current Patterns in Health Care Non-Competes

Most states permit non-competes in some form.[2] In states where noncompetes are permitted, almost all have general restrictions limiting their scope to reasonable restrictions on geography, time, and job duties.

The new laws regulating the use of non-competes with medical professionals, however, are much more varied in scope, approach, and enforceability.

Scope

State laws regulating non-compete agreements in health care span the full spectrum – from narrowly covering only licensed physicians[3] and a limited number of other medical professions[4]—often registered nurses—to encompassing up to 28 distinct health care professions.[5]

Even within statutes applicable only to physicians, distinctions arise based on specialty or who is a party to the agreement. For instance, Tennessee[6] excludes emergency medicine specialists from its non-compete restrictions, while Indiana’s[7] new law, effective July 1, 2025, applies only to agreements between physicians and a hospital or its affiliate.

Diverging Patterns

Together with those states maintaining longstanding prohibitions, certain states have recently adopted a variety of new regulatory models governing noncompetes for health care practitioners:

- Blanket Prohibitions: Some states[8] outright void non-compete agreements with select medical professionals, such as Arkansas (effective August 5, 2025), while others[9] like Wyoming’s[10] new law, effective July 1, 2025, void agreements upon termination of employment. Meanwhile, Indiana’s new law was careful to only cover non-competes entered into on or after July 1, 2025, excluding any amendments or renewals made to existing agreements.

- Defined Limitations: Other states allow non-competes with medical professionals, but place limitations on what is a “reasonable” duration and geographic scope. Most commonly, a non-compete may last up to 1 year in duration after termination, but non-competes with health care providers in Tennessee[11] may last up to two years. Some states define geographic limitations using fixed political boundaries. For example, Louisiana[12] requires non-competes with physicians to be limited to specific parishes, while Florida’s[13] approach is more complex, requiring an analysis of the number of specialists in a county. Other states impose restrictions based on a defined radius from a practitioner’s primary practice location. For instance, Maryland[14] limits the geographic scope to a ten-mile radius (effective July 1, 2025), Connecticut[15] to 15 miles, and West Virginia[16] to 30 miles with limited exceptions. Most recently, on June 20, 2025, Texas enacted a law limiting the geographic scope to a five-mile radius from the location where the physician primarily practiced before the contract or employment terminated.[17]

- Enforceability: Several jurisdictions place conditions on enforceability that hinge on the circumstances surrounding the termination of the agreement. In Indiana[18], for example, non-competes are unenforceable if the physician is terminated without cause, the physician terminates for cause, or the contract expires and the parties have fulfilled the obligations of the contract. Connecticut[19], on the other hand, conditions enforceability on whether a bona fide renewal offer was made prior to the expiration or whether the termination was for cause. Others place restrictions on buy out provisions.

- Hybrid Approach: States such as Maryland take a hybrid approach, marrying compensation thresholds commonly used in generic non-compete laws with medical-specific limitations. Maryland’s[20] law governing non-competes with medical professionals only applies if the professional earns $350,000 or less in annual compensation, must be licensed to practice, and provides direct patient care. Colorado’s[21] upcoming law (effective on August 6, 2025) excludes certain health care providers from general non-compete exemptions, effectively barring such agreements regardless of compensation.

Shifts on the Horizon

Several states are poised to further reshape the medical noncompete landscape:

- Most recently, on June 20, 2025, Texas[22] enacted a law further limiting the use of non-competes with licensed physicians, which among other requirements, requires agreements to include a buyout cap not to exceed the practitioner’s annual salary and wages. The law takes effect on September 1, 2025, and in addition to physicians, will now cover dentists, certain nurses, and physician assistants.

- Florida[23] passed a bill in April that was just sent to the governor on June 18, 2025, which expands non-compete limitations to cover employees for longer with a potential larger geographic scope, but interestingly expressly excludes health care practitioners.

- On June 11, 2025, the Nevada governor vetoed[24] a bill that would have prohibited non-compete agreements with patient-facing health care providers. It remains to be seen if the veto will be overridden.

Factors Shaping Varying Approaches

This new collection of statutory limitations on medical practitioner noncompete agreements across the country appears to derive from several different factors. First, physicians and other health care professionals often have strong advocacy and lobbying organizations that represent their interests and can assist in bringing their prioritized legislation to the ears of lawmakers in their respective states. This can result in greater protections for health care workers from noncompetes than for other workers and professionals.

Secondly, the arguments for limiting noncompetes in the health care sector often resonate outside of the economic world of health care practitioners in ways that similar arguments for other workers may not. For example, practitioners’ arguments that they be permitted to continue to provide services in a given market or be permitted to continue serving certain patients are often couched in terms of patient care continuity and the need for a particular community to maintain access to limited health care services. Such advocacy often leads to discussions involving more stakeholders than just the health care employer and employee or contractor.

Thirdly, there remain the legitimate competing interests of the health care employers and contractors, which are similar to those in other fields, but often take on outsized importance in the world of health care. For example, employers may have invested heavily in departing practitioners and provided them with access to the company’s confidential information, customer relationships, specialized training, and company good will. Oftentimes, the training and information relate to cutting edge technologies, given the rapidly evolving state of modern health care. Consequently, employers and contractors with health care professionals may seek to protect that investment by preventing these departing practitioners from going into roles of direct competition where they might unavoidably take advantage of those investments to their former employers’ competitive disadvantage.

Market Impact

Any time a law is passed that limits or permits greater competition, market forces are distorted. Given this mosaic of new laws targeting one key sector of the economy, one that nonetheless impacts every American, we can expect markets distortions to appear, as well as a shift in employer, practitioner, and consumer incentives.

Moreover, given the complexity of the health care market, these new laws will undoubtedly result in unintended consequences that those passing these laws could not have foreseen. Even as these laws are designed to protect certain interests, they will inevitably impact others in ways that cannot necessary be controlled. In the end, we are likely to see a series of trade-offs, rather than solutions,[25] with the need to revisit many of these laws as their full impact on all affected parties becomes clear.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the regulation of non-compete agreements in the health care sector continues to evolve rapidly at the state level. While some states have adopted comprehensive bans, others have opted for more nuanced frameworks that balance enforceability with public policy considerations. As more states revisit their statutes, the legal landscape is likely to become even more complex, requiring careful attention to jurisdiction-specific requirements.

Employers and other companies contracting with health care professionals should seek legal guidance regularly and often to ensure their agreements with health care professionals meet state law.

[1] Appeals challenging the FTC rule are currently stayed. Ryan v. Fed. Trade Comm’n, No. 24-10951 (5th Circ. Mar. 12, 2025) ECF No. 210 (Granting order to stay appeal for 120 days); Properties of the Villages, Inc. v. Fed. Trade Comm’n, No. 24-13102 (11th Circ. Mar. 20, 2025) ECF No. 117 (Granting order to stay appeal for 120 days). Also, on February 14, 2025, the acting NLRB General Counsel rescinded previously issued GC memorandums related to non-competes. GC 25-05; Rescinded Memos GC 23-08 and GC 25-01.

[2] With limited exceptions, the following states generally prohibit the use of non-compete agreements: California (Cal. Bus. and Prof. Code §§ 16600 – 16600.5), Minnesota (Minn. Stat. § 181.988), North Dakota (N.D. Cent. Code § 9-08-06), and Oklahoma (Okla. Stat. tit. 15, §§ 217 to 219B). Colorado also tightly restricts the use of noncompetes and permits them only in limited circumstances such as, e.g., highly compensated workers, the sale of a business, and to protect a company’s trade secrets. See Colo. Rev. Stat. § 8-2-113.

[3] E.g., Delaware (Del. Code tit. 6, § 2707), Florida (Fla. Stat. § 542.336), Louisiana (La. Stat. § 23:921(M – O)), West Virginia (W. Va. Code §§ 47-11E-1 to 5), and Wyoming (S.F. 107 to be codified at Wyo. Stat. § 1-23-108).

[4] E.g., Colorado (S.B. 83 to be codified at Colo. Rev. Stat. § 8-2-113), Connecticut (Conn. Gen. Stat. §§ 20-14p, 20-101d, and 20-12k), Massachusetts (Mass. Gen. Laws ch. 112, §§ 74D, 12X, 129B, and 135C), and New Hampshire (N.H. Rev. Stat. §§ 315:18, 326-B:45-a, and 329:31-a).

[5] South Dakota (S.D. Codified Laws §§ 53-9-11 and 53-9-11.2).

[6] Tenn. Code § 63-1-148(d).

[7] S.B. 475 amending Ind. Code § 25-22.5-5.5 et seq.

[8] E.g., Arkansas (Ark. Code § 4‑75‑101), Massachusetts (Mass. Gen. Laws ch. 112, §§ 74D, 12X, 129B, and 135C), New Hampshire (N.H. Rev. Stat. §§ 315:18, 326-B:45-a, and 329:31-a), and Rhode Island (5 R.I. Gen. Laws §§ 5-37-33 and 5-34-50).

[9] E.g., New Mexico (N.M. Stat. § 24A-4-2) and South Dakota (S.D. Codified Laws §§ 53-9-11 and 53-9-11.2).

[10] S.F. 107 to be codified at Wyo. Stat. § 1-23-108.

[11] Tenn. Code § 63-1-148(a)(2).

[12] La. Stat. § 23:921(M – O).

[13] Fla. Stat. § 542.336.

[14] Md. Code, Lab. & Empl. § 3-716(2)(ii).

[15] Conn. Gen. Stat. §§ 20-14p(b)(2)(A)(ii); 20-101d(b)(2)(A)(ii); and 20-12k(b)(2)(A)(ii).

[16] W. Va. Code §§ 47-11E-2(a)(2).

[17] S.B. 1318, 89th Reg. Sess. (Tex. 2025).

[18] Ind. Code § 25-22.5-5.5-2(b).

[19] Conn. Gen. Stat. §§ 20-14p(b)(2)(B); 20-101d(b)(2)(B); and 20-12k(b)(2)(B).

[20] Md. Code, Lab. & Empl. § 3-716(b)(1).

[21] S.B. 83 to be codified at Colo. Rev. Stat. § 8-2-113.

[22] S.B. 1318, 89th Reg. Sess. (Tex. 2025)

[23] H.B. 1219, 127th Leg., Reg. Sess. (Fla. 2025).

[24] S.B. 378, 83rd Leg., Reg. Sess. (Nev. 2025).

[25] See Thomas Sowell, A Conflict of Visions: Ideological Origins of Political Struggles.